It is presumptuous to assume that the patterns and roles in physician-patient relationships that have been in place for a half a century and more still hold true. However, culture (a composite of the customary beliefs, social forms, and material traits of a racial, religious or social group) is not static and autonomous, and changes with other trends over passing years. In countries with ancient civilizations, rooted beliefs and traditions, the practice of paternalism ( this term will be used in this article, as it is well-entrenched in ethics literature, although parentalism is the proper term) by physicians emanates mostly from beneficence.

Resistance to the principle of patient autonomy and its derivatives (informed consent, truth-telling) in non-western cultures is not unexpected. A physician’s obligation and intention to relieve the suffering (e.g., refractory pain or dyspnea) of a patient by the use of appropriate drugs including opioids override the foreseen but unintended harmful effects or outcome (doctrine of double effect). This is particularly important and pertinent in difficult end-of-life care decisions on withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment, medically administered nutrition and hydration, and in pain and other symptom control.

The practical application of nonmaleficence is for the physician to weigh the benefits against burdens of all interventions and treatments, to eschew those that are inappropriately burdensome, and to choose the best course of action for the patient. This simply stated principle supports several moral rules – do not kill, do not cause pain or suffering, do not incapacitate, do not cause offense, and do not deprive others of the goods of life. Nonmaleficence is the obligation of a physician not to harm the patient. However, complying with these standards, it should be understood, may not always fulfill the moral norms as the codes have “often appeared to protect the profession’s interests more than to offer a broad and impartial moral viewpoint or to address issues of importance to patients and society”.

To reduce the vagueness of “accepted role,” physician organizations (local, state, and national) have codified their standards. A pertinent example of particular morality is the physician’s “accepted role” to provide competent and trustworthy service to their patients.

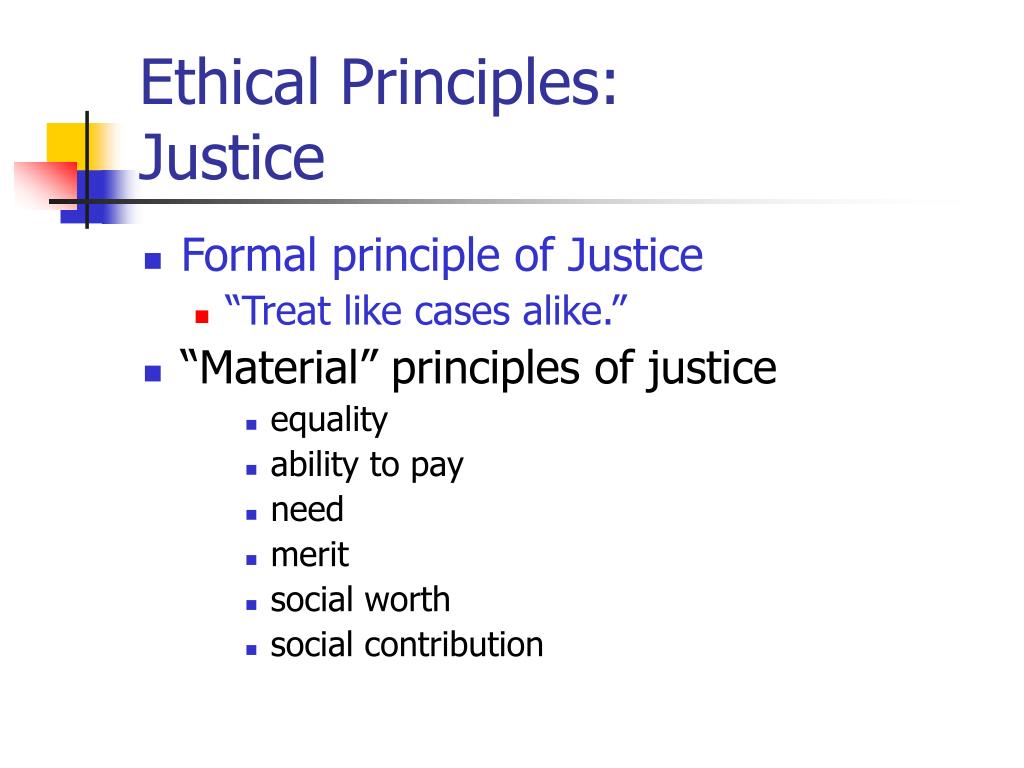

#Ethical principle justice professional

Particular morality refers to norms that bind groups because of their culture, religion, profession and include responsibilities, ideals, professional standards, and so on. Some moral norms for right conduct are common to human kind as they transcend cultures, regions, religions, and other group identities and constitute common morality (e.g., not to kill, or harm, or cause suffering to others, not to steal, not to punish the innocent, to be truthful, to obey the law, to nurture the young and dependent, to help the suffering, and rescue those in danger). Normative ethics attempts to answer the question, “Which general moral norms for the guidance and evaluation of conduct should we accept, and why?”. Ethics is a broad term that covers the study of the nature of morals and the specific moral choices to be made.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)